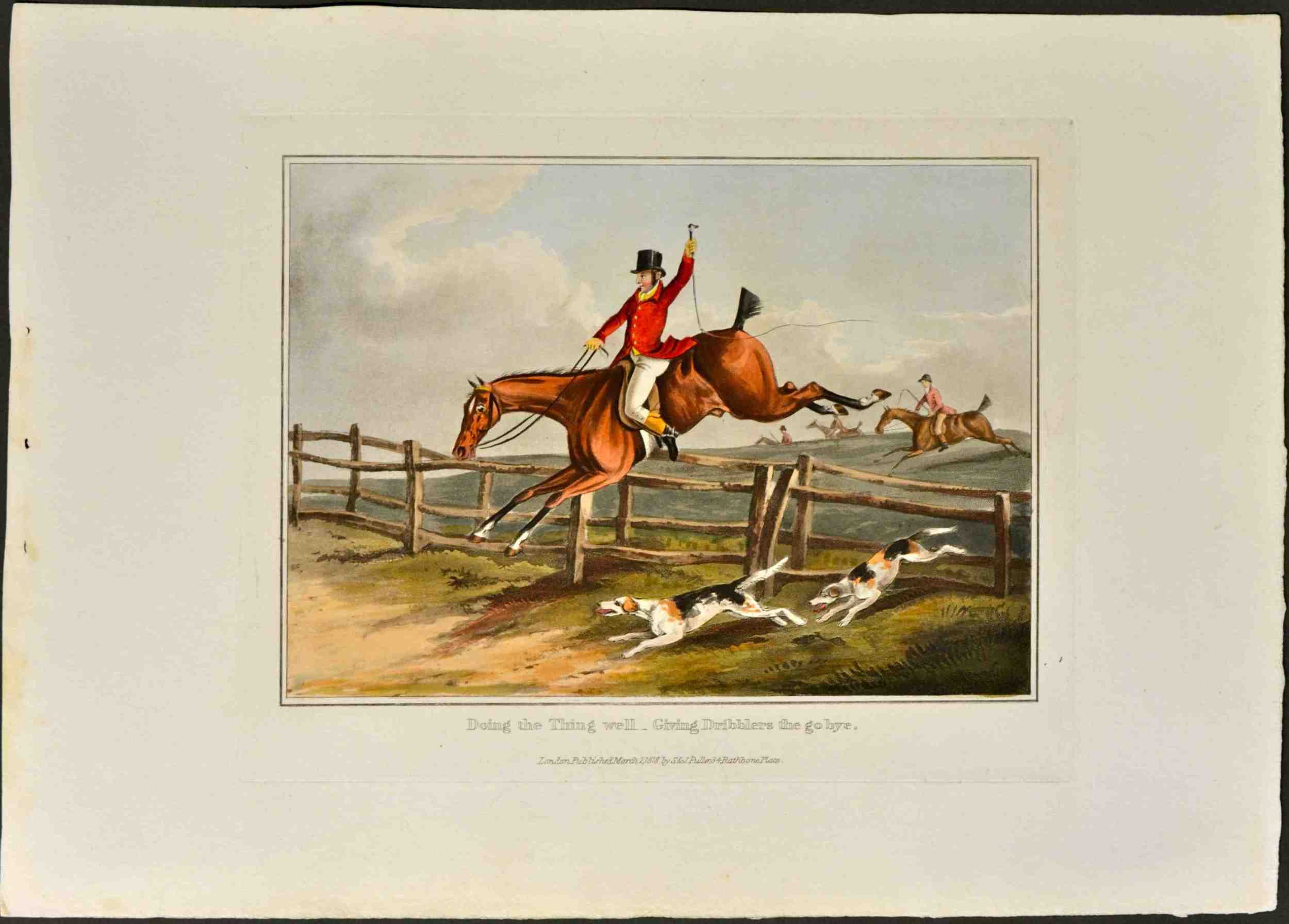

Hunting may be a fall sport—but art conservation is a year round activity. Whether he was drawing, etching, or painting his famous hunting scenes, Henry Thomas Alken (English, 1785–1851), judging by the amount of work he produced during his career, was always, like us, working. The Conservation Center is always thrilled to treat high quality works by artists such as Alken. Not only can we appreciate his skilled artistry, but we can also admire the humorous point of view through which he saw his subject matters.

Born in Soho, Westminster in 1785, Henry Thomas Alken was what can only be described as an “artist’s artist.” He developed a lively career, which began under the pseudonym “Ben Tallyho” or “Ben Tally-O”—creating prints for printsellers, and his works reached high demand in 19th century England. Additionally, Alken provided plates for publications such as The National Sports of Great Briton, first issued in 1821. Often his work consisted of satirical depictions of the foibles of aristocracy with titles such as Humorous Specimens of Riding (1821), Symptoms of Being Amused (1822), and Symptoms of Being Amazed (1822). He collaborated with his friend and sports journalist Charles James Apperley, who also went by Nimrod. Nimrod’s Life of a Sportsman, which contained more than 30 of Alken’s etchings, was published in 1842. It wasn’t until after his death, in 1851, that Alken’s work was accepted amongst museums and galleries. Today his prints can be found in such prestigious museums as The Tate and The British Museum, offering patrons a smirk and a chuckle.

Chicago-area collector Norman Bobins’ collection of books and prints includes numerous examples of 19th century British sporting art. In 2013, he acquired two sets of Alken prints, titled Doing the Thing; and the Thing Done, in a Series of Sporting Plates (11-page, loose bound lithographic plates), and Akermann’s Sporting Anecdotes (20-page, bound lithographic plates and drawings), which were all recently conserved here at The Center. Akermann’s also included an original pencil and an original watercolor, studies relative to the prints. Both volumes unfortunately sustained water damage previous to acquisition, which was warranted by their relative rarity and inclusion in a collection with a substantial number of complementary pieces.

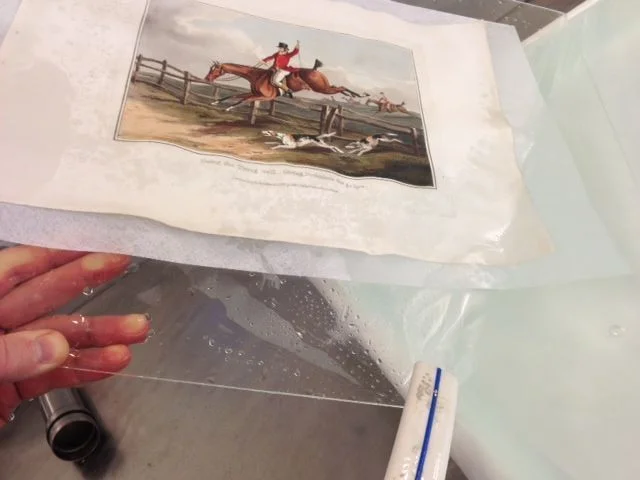

The water damage caused the Alken volume cover pigments—mostly red—to bleed onto the work, around the print’s edges and corners. Many steps were taken in order to return the works to their original splendor. First, the paper conservator dry cleans the sheets by blotting away dust particles using a dry sponge. After which, a gentle solvent is applied to areas where the damage is most focused. This is a treatment described by the conservator as “light bleaching,” and prevents color from bleeding further into the body of work.

Bleaching requires a substantial amount of time and, if the conservator is unhappy with the results, it will need to be done twice. After bleaching, the piece is submerged in water in a meticulous process called “floating.” In this case, the conservator must absolutely not allow the artist’s watercolor to fully submerge—but soak only the edges where the color has bled. If it is completely submerged, the artist’s intended work will be compromised because watercolor is a fugitive medium. This can take up to 12 hours and sometimes needs to be repeated. When submerged in water, one can actually see with the naked eye the breakup of the pigment.

Now that each piece has been “bleached” and “floated” it needs to be dried in a very specific manner. If the piece dries unevenly, it will create tidelines—markings of where the water has migrated throughout the paper. To accomplish the drying process properly, the print is laid on a blotter designed to absorb moisture at an even pace. The print will then re-humidify before drying on a blotter. This is usually the last step unless the piece is uncommonly stubborn and insists upon drying unevenly. In this case, the work is placed into an envelope made of Gore-Tex, which ensures an even drying process by allowing the correct amount of decreasing humidity to affect the paper.

After this process, the lithographs are as vivid and witty as it was the day Henry Thomas Alken, aka Ben Tally-O, put his signature on them—no doubt with a wink and a smile for all. The result of their renewal due to conservation efforts at The Center made a fine contribution to Mr. Bobins’ overall collection.