Treating a Forefather to Socialist Realism: A New Acquisition from The Chazen Museum

This icy, intricate oil painting by Latvian artist, Arkadii Soloviev, came to The Center with age-related damage – small losses around the edges of the fraying composition board upon which it was executed, and a tenacious layer of discolored varnish. The gilded frame also exhibited small losses and abrasion. The painting came to us from the Chazen Museum of Art in Madison, which houses the second-largest collection of art in Wisconsin, including more than 22,000 diverse works of historical importance.

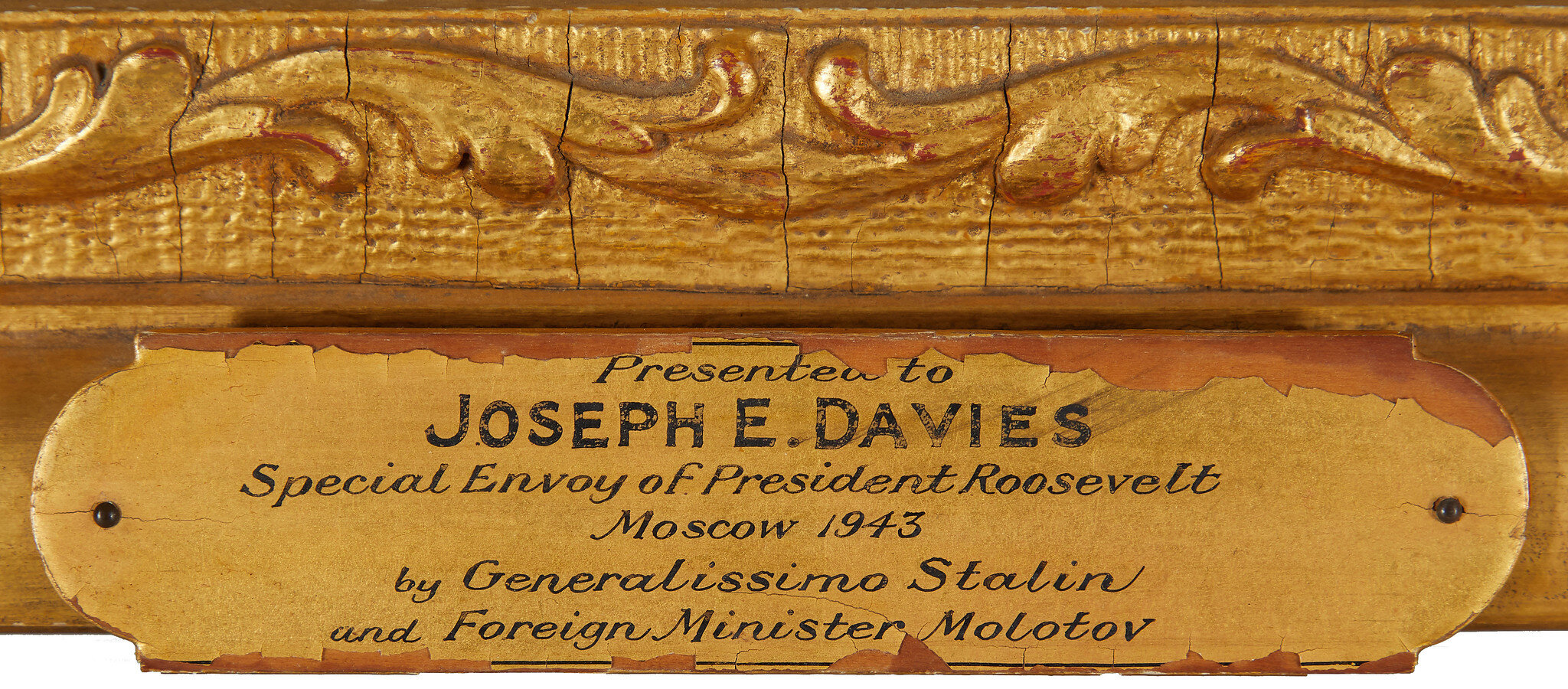

Reconnaissance Attack was painted by Soloviev in 1942. The engraved plate affixed reads: "Presented to Joseph E. Davies Special Envoy of President Roosevelt Moscow 1945 by Generalissimo Stalin and Foreign Minister Molotov.” It originates from the collection of Davies, the US Ambassador to the (then) Soviet Union, gifted to him by Molotov and then passed down by descent through the estate of US Senator Joseph Davies Tydings. The Chazen Museum acquired it earlier this year from the Tydings estate through Alex Cooper Auctioneers thanks to the Walter A. and Dorothy Jones Frautschi Endowment Fund.

The painting itself is a strong example of work produced by AKHRR, or The Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia, which then led the way to Socialist Realism. Founded in Moscow in 1922, it depicted the everyday life of working people in Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution in a realistic, documentary manner. Socialist Realism was imposed by Stalin after the death of Lenin in 1924 and was a visual language characterized by viciously optimistic pictures of Soviet life in a realist style.

“From the start, the new Soviet state enlisted art to serve an educational and instructional function to reinforce cultural values. Communist Party leaders firmly enforced the doctrine that the arts must serve society by educating and inspiring the masses, and artists were instructed to look to art of the past. Works of art had to reveal the spirit of socialism and reflect the Communist Party viewpoint. Its purpose was to further the goals of communism and to glorify the proletariat’s (the working classes) struggle toward socialist progress. This new Soviet art should be optimistic, heroic, and make visible the spirit of socialism for both national and international audiences. Its practice was marked by strict adherence to party doctrine and to conventional techniques of realism.”

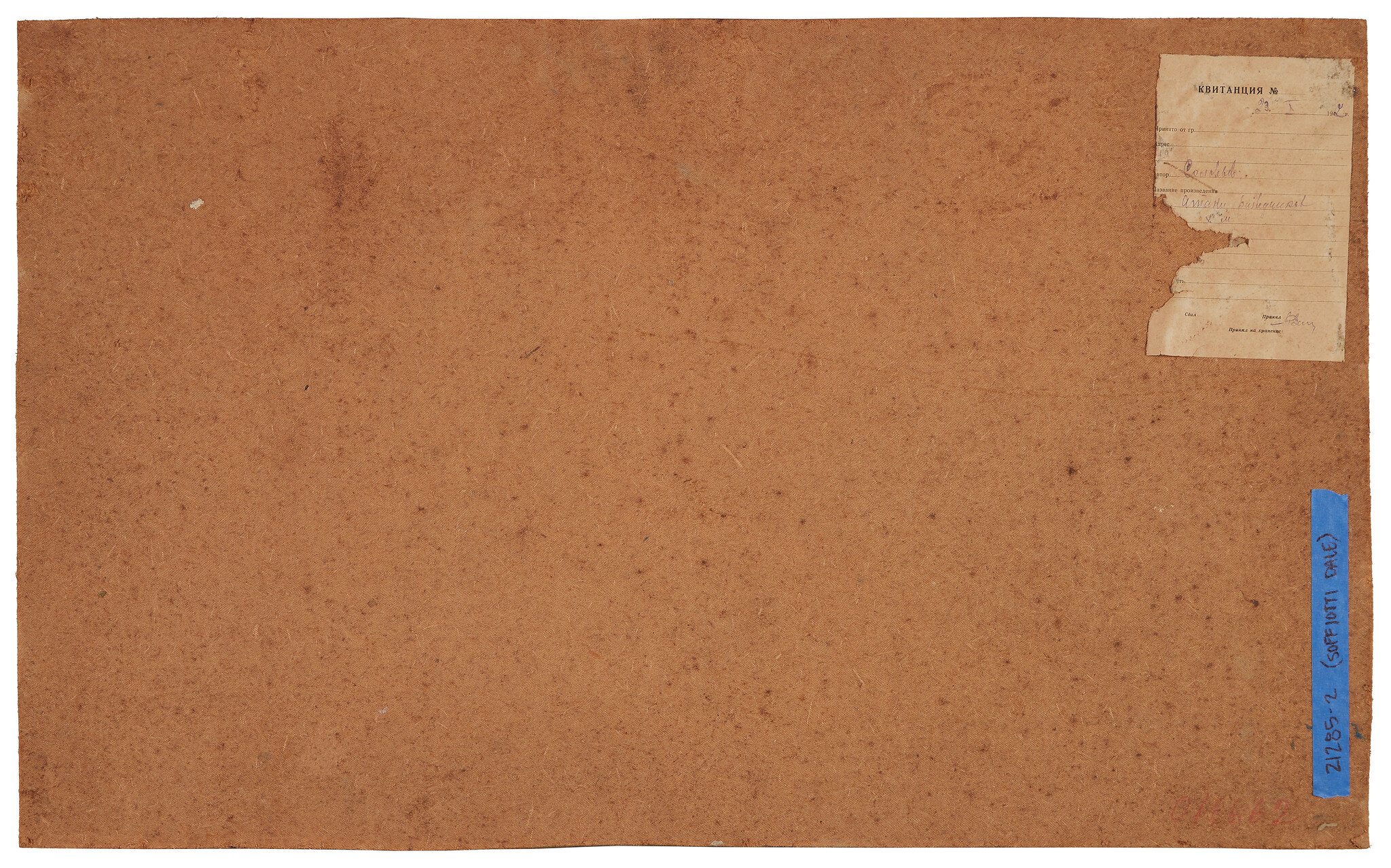

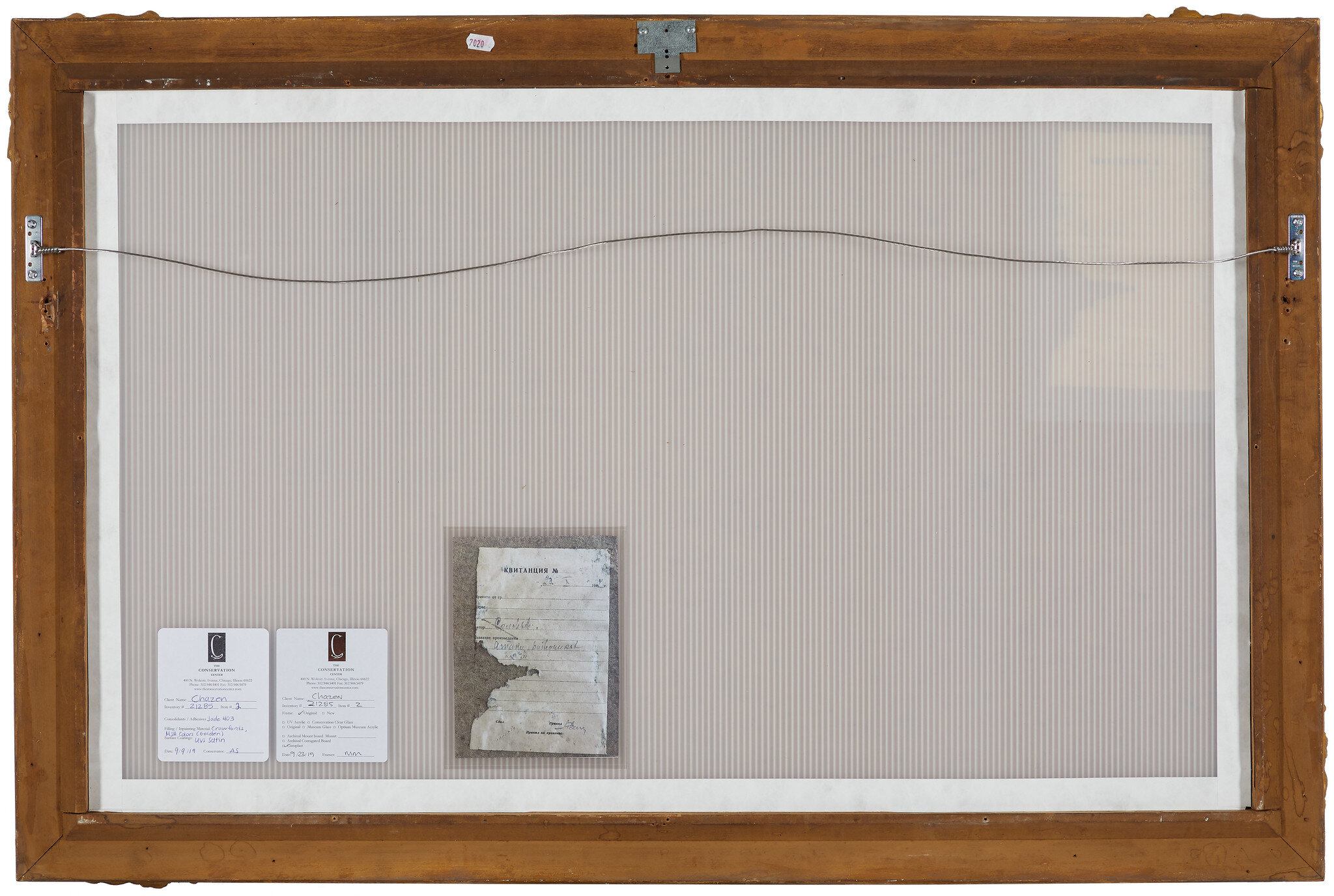

History aside, this work presented itself to our conservators as two separate pieces to be addressed and treated: the painting itself, and the frame it was housed in. To treat the painting it was first photographed, and then the label on the back (in Russian) was protected with Mylar encapsulation to preserve it. The edges of the composition board were consolidated using conservation grade adhesives, and the painting was surface cleaned to remove grime. The reverse was cleaned as well, using a soft brush and vacuum. Next, the varnish layer was removed with organic solvents, and the losses around the edges were filled and textured using reversible, conservation-grade fill materials.

Mid - varnish removal.

A coat of varnish was applied to saturate the paint layer before inpainting was carried out in areas of loss and abrasion. Finally, another coat of varnish was applied to integrate the surface gloss.

One of our painting conservators working on the piece.

As with any treatment, repairs and previous treatments are visible under black light.

The frame was a different story. Composed of wood, compo, gesso, and gold leaf, it needed to be stabilized and the open miters filled to begin its treatment process.

Damage to the frame is clearly visible before treatment.

The frame was then mechanically cleaned, and minimally solvent cleaned. Scratches and abrasions were inpainted to emulate the surrounding surface. Losses in cast decoration were re-cast using conservation grade material and then filled and inpainted. These new restorations were patinated to match the original work. Aside from cleaning and small areas of rebuilding, the finish was left in it’s present state. The losses in the nameplate were filled, inpainted, and ingilded, which is the same theory as the inpainting process but with gold leaf. Finally, a Coroplast backing board was attached to the reverse to provide additional protection.

The finished work.

The Soloviev has been returned to The Chazen Museum, and we look forward to seeing it displayed. Its complex and interesting history are only a part of what makes this work so intriguing – the intricate frame in contrast to the cold, military subject matter alludes to its own internal conflict and cultural importance.