Recently, a 10th century Greek Codex—which contains portions of the New Testament Gospels of Luke and John—arrived at our conservation lab, and we, admittedly, are truly impressed. This rare book belongs to Andrews University in Berrien Springs, Michigan, a Bible-based university supported by Seventh-day Adventist Church.

The Codex, housed in The Suhrie Bible Collection at Andrews University’s Center for Adventist Research, is a part of a grouping of 132 Bibles and scrolls dating mostly from the 14th century AD to the 19th century, with a few from the 20th century. The research center’s larger collection is the most complete collection in the world of Seventh-day Adventist history, culture, and theology. Over 60,000 books, 25,000 periodical volumes, plus thousands of smaller print items, audio-visuals, and manuscript collections are included.

In January 2014, the university experienced its worst fear—an unexpected pipe burst. The Codex, along with quite a few other rare volumes from the Suhrie Bible Collection, was on exhibit in the Center for Adventist Research. Some building renovations took place on the next level, and that construction jarred a copper water pipe that was corroded. The disturbed pipe began to leak water, which eventually followed various building components and ended up leaking water into the Bible exhibit case. When university officials discovered the situation, they interleaved as much as they could with blotting paper and placed the affected volumes into a deep freeze. Ultimately, Andrews University was led to The Conservation Center and quickly transferred the affected volumes, including the Codex, for drying and conservation work. Also affected in this incident was a 1553 Tyndale version of the New Testament and the 3rd edition of the King James Bible.

A Codex usually refers to a manuscript transcribed by monks in book form as a more stable alternative to scrolls. It is clear that this is an important object, not just as a historical artifact, but also as a valuable asset to the study of Christianity. Jim Ford, the Associate Director for the Center For Adventists Research, explains, “Being a Seventh-day Adventist Church-based higher education institution, the Bible, in all its forms, is very important to us. A piece such as this Codex is a tremendous asset in that it allows our visitors to understand better how they came to have the Bible they have today.”

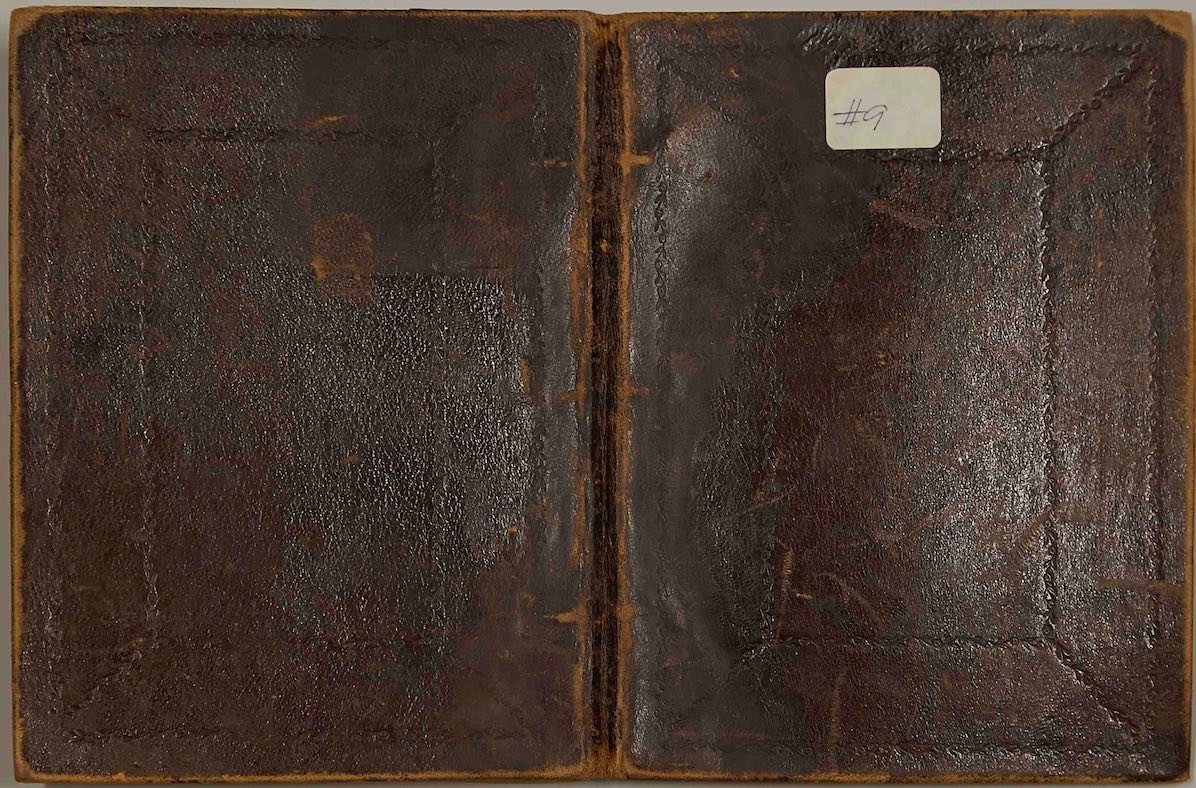

This particular example is bound with leather covers and decorative blind-tooled paneling, which can be thought of as ornamental brandings into leather. The book itself is comprised of mostly vellum. Made of calfskin, it was the highest quality parchment of the time. The book was also written using traditional iron gall ink, which was the standard in drawing and writing ink because of its permanence and water resistance abilities. In addition, some beautiful gold leaf also adorns the Codex. Due to the time spent crafting the book with these high quality materials, the importance of this object to the time period in which it was made is self-evident.

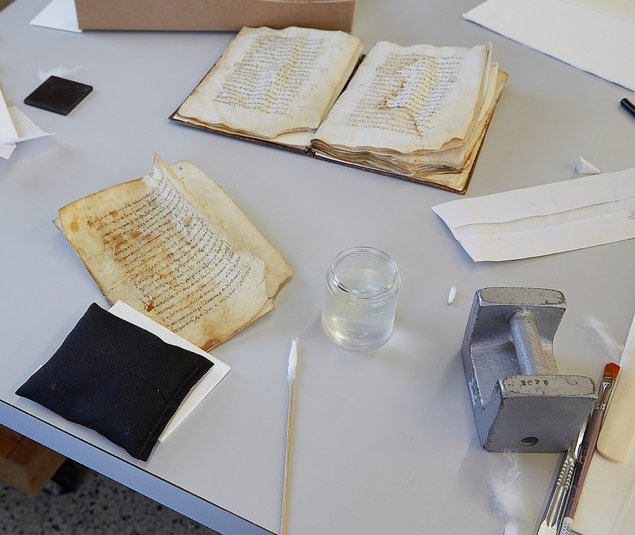

Comprised of 37 bound vellum sheets and 10 parchment sheets at the ends, our conservators had their work cut out for them. In addition to the water damage, the codex needed restoration common for manuscripts of this nature. Because of the porous nature of animal skin and the short fibers in the papers, the materials used in this codex actually expand and contract as the humidity and temperature change, and have been doing so for the last thousand years. Significant work needs to be done to stabilize the page warping and to prevent brittleness and cracking. For years after being penned, the Codex was probably used almost daily in religious practices resulting in losses of entire folios, as well as to the lower corner of multiple pages (due to additional traction of turning the pages and the oil on one’s hand, these were probably the only area of the Codex that was regularly handled). Compounding the damage, rodents nibbled away at the corners of the page, something surprisingly common to books made of vellum as they age.

Additionally, the entire piece needs to be rebound and cleaned up, as it has sustained discoloration and staining over the years, as well as some evidence of mold. However, when approaching the cleaning of such an old and fragile object, it is sometimes better to leave stains and discolorations and work to stop further decay, rather than damage the original integrity of the piece.

This project is expected to eclipse 400 hours of conservation work between The Center’s paper and the rare books conservation departments. We’re honored to be treating such a sacred volume, and over the next few months we encourage you to observe the conservation process from beginning to end via our Instagram and Vimeo channel. A follow up story will be featured in a future issue of our newsletter.